Journal

How the Herter Brothers Revolutionized Interior Design

When it comes to furniture designers in the United States, the Herter brothers stand apart with their ornate, cross-culturally inspired creations. The Herter brothers started their company in February of 1864. The company was known for extravagant wooden chairs, cabinets, tables, and other furnishings until it’s closure in 1907. Gustav and Christian Herter had a fairly simple upbringing during an explosive time in history that inevitably led to amazing furniture, which contributed positively to the interior architecture profession, society, and culture as a whole.

On May 14, 1830 Johanna Christiana Maria Barbara Hagenlocher gave birth to a healthy Julius Gustav Alexander Hagenlocher in Stuttgart, Germany. The bustling city of Stuttgart sits at the bottom of Germany and was the capital of the kingdom of Wurttemberg. Little is known about Gustav’s biological father. Gustav’s mother took sole care of him. Eventually she met Christian Herter, a humble woodworker and cabinetmaker. Christian’s official title was an “ebenist.” An ebenist was a highly skilled craftsman qualified to make case pieces such as chests and cabinets decorated with fancy inlay and wonderful veneers. In 1835, the couple was wed. Both young Gustav and his mother took the last name Herter upon the marriage. This man served as a father figure for both brothers and would ultimately lend his name to the men’s notable furniture company. On January 8, 1839 Christian Augustus Ludwig Herter became the first child of Christiana and Christian’s union. A few years later the family welcomed a baby girl to the family. Marie Emilie Elise Herter was born on the 13th of May. All three children grew up in Stuttgart. Stuttgart is where Gustav and Christian both learned the basics of carpentry and gilding, a technique that involves applying gold leaf to furniture. It is assumed, by most historians, that the brothers learned most of this from Christian. It is unclear where both boys got such great schooling in their craft; however, it is apparent they were both taught well.

The Revolution of 1848 hit Germany when Gustav and Christian were eighteen and nine. A series of political upheavals swelled in most of Europe and some of Latin America. Many were dissatisfied with leadership. Revolutionists were also upset with the regrouping of the aristocracy, royalty, army, and the peasants. Reactionary forces regained control of Europe within a year; however, many left the country before order was restored. There was a massive surge of migration from Europe. These educated, skilled people were referred to as the “Fourty-Eighters.” Most “Fourty-Eighters” were seen differently than other groups of immigrants. They were welcomed contrarily because their cognitive abilities surpassed other major groups of newcomers to the United States. Gustav left Stuttgart during the year of the revolution and settled in New York.

A young Gustav arrived in America when this country was the most powerful and richest nation in the world. At this time, the field of decoration and furniture, design and ornament, and other manufacturers was very dramatically divided. French design was extravagant and expensive. It was customary for French art to be covered in silks and hand-painted ceramics. The French design aesthetic was that of privilege and luxury. English design was associated with morality, and an elegant modesty. English tapestries, and paintings were honest. Eastern design was rare in the United States and did not play a part. Art, at this time in America, could be classified easily; there was minor overlap in design origin.

Gustav only lived in New York for what must have been a magnificent two years before he applied for citizenship on June 29, 1850. Not much is know about the oldest brother’s early time spent in the United States. Federal records show that Gustav referred to himself as a Bildhauer, or sculptor. It is also believed that he was one of the first men in America to take on the title of decorator. Most accounts connect Gustav Herter as a resident of an area on the Lower East Side of Manhattan known as “Little Germany.” This is where he stood out among other cabinetmakers and caught the eye of Edward W. Hutchings, a prominent businessman, who introduced Gustav to others advancing in the trade. Soon after, Erastus Bulkley and Gustav established a firm called Bulkley & Herter. Two pieces were designed and shown in the New York Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1853: an oak buffet, and an oak Gothic Revival bookcase. Other influential furniture was made and overseen by the firm until it was dissolved in 1858. It was then that Gustav declared sole proprietorship.

The company grew considerably over the next couple years. In 1860, Gustav Herter employed one hundred men and owned a massive stockpile of oak, mahogany, rosewood, and walnut. As the company grew larger and larger, it is safe to assume that most of the actual carving and sculpting of the sofas, chairs, tables, and such was now being done by hired workmen under the supervision of Gustav. In 1864, Christian and Gustav become business partners and the firm changes its name from Gustav Herter to Herter Brothers.

The main distinction other interior design companies and the Herter Brothers firm was their attention to the room as a whole. Gustav and Christian were very interested in coordinating entire interiors. They helped with everything in a prospective space from the woodwork, ceiling decoration, seating, tables, flooring, and upholstery. This vision of the design of a space as a whole would catch on and change the field of interior design for future interior architects.

The Herter Brothers designed for the wealthy. Their elite clients fell in love with the intricacies of the men’s pieces. The Herter Brothers designed bedsteads with fancy floral images gilded across ebonized cherry and side chairs with maple legs completely gilded adorned with glass jewels. Their cabinets, nightstands, and desks were unique in their particulars and became clearly recognizable as Herter Brother creations. Contrasting immeasurably from the simple furniture of the Shakers, and steps beyond the Carver chairs, the Herter Brothers offered luxury to the American people. The boys from Germany capitalized not only on the spirit of entrepreneurship that the United States offered, but also on the powerful mindset emitted from the citizens there. The Herter Brothers furniture projected clearly power and wealth with its stained inlays and lavish marquetry. Gustav and Christian’s furniture personified an attitude that the United States embodied then. Clients of the firm were the most visible and affluent of the era. The White House held Herter furniture, as did William Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, J. Pierpont Morgan, and Mrs. Mark Hopkins. Most of the firms remaining works are now housed in art museums across the country.

Herter Brothers furniture was also innovative in that it merged many styles of design into single pieces. This was revolutionary in the 1860’s. They were combining the blacks and straight lines of Japanese architecture with ornate carvings of leaves and branches seen in French design. Their pieces held notes of German, French, Asian, and American influence. This was groundbreaking; it challenged other artists in their thinking. This concept of cross-cultural furniture would eventually eek its way into paintings, sculptures, textiles, and fashion. The Herter Brothers revolutionized the way designers thought.

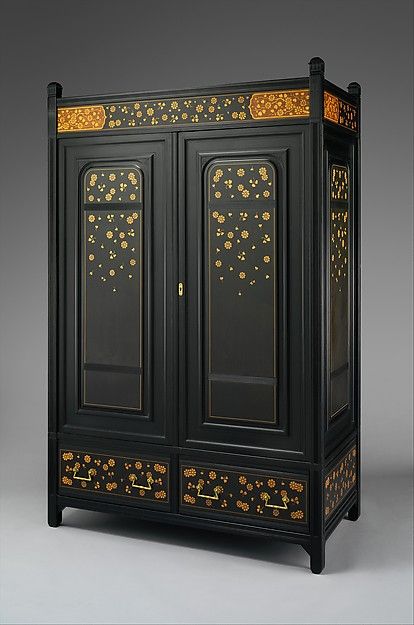

Everything designed by the firm stands out among other furniture made before, during, and even after its time. The design aesthetic of Herter is unique. A learned interior architect would be able to identify a chair or cabinet by the brothers easily. There are five pieces that are more commonly called upon to showcase their work. It is interesting to note that there are no lasting photographs, or drawn portraits of either brother; while, pictures of their art and the art itself are still around today. This is an excellent example of how prominent their designs were. The furniture became more famous than the furniture designer. The men were outlived by their work. The wardrobe of ebonized cherry, a cabinet lined in silk velvet, a beautiful folding screen, an exhibition stand done in burled walnut and an armchair from 1874 are five of the brothers most famous works.

The Herter Brothers fashioned an ebonized cherry wardrobe around 1875. It had Chinese and Japanese styled ornamentation. The huge armoire now sits in The Metropolitan Museum of art. It has white oak and yellow poplar adorning all front facades that read as a blooming set of branches. This piece is a wonderful representation of their Anglo-Japanese design.

A cabinet made mostly of maple and accented with marquetry of white pine, cedar, and ash showcases the Herter Brothers’ majestic aesthetic. The piece, which is 53½ inches long, is ornamented with gilding, paint, glass, and brass. The doors of the cabinet have panels with butterfly motifs and gold leafed, carved flowers. Near the corners near the top the sculpture carved in two lion’s heads ferociously growling at one another. This furniture piece is an excellent example of how the Gustav and Christian collaborated different types of design together.

Another art piece of great importance made by the Herter Brothers was a meticulously handcrafted folding screen. This screen was probably made for the reception room of the Mark Hopkins residence in San Francisco. It was designed to sit alongside the armchairs in that space. The frame of the divider is ebonized cherry and the fabric stretched across its frame is made of silk velvet and woven wool and silk. The color scheme of the screen is that of gold, burgundy, and butter yellow. These colors were traditional of Turkish interior design. The patterned portion of the screen depicts rose-colored, white, and yellow tulips, irises, and daffodils. The screen is 72½ inches tall. It was definitely a statement piece that even in the Hopkins’ residence would have stood apart.

It is important to remember that the Herter Brothers firm was originally the brainchild of the older brother, Gustav Herter. The critical, make-or-break times during the company’s start off could have easily ended in disaster if not for Gustav’s excellent craftsmanship. An exhibition stand made during the early years of the older brother’s company was launching is now held in The Detroit Institute of Arts. The stand, intended for the display of drawings or prints, was craved from burled walnut, oak, and white pine. It was lined in felt, and silk velvet. The stand has elements of Ancient Greek and Renaissance design. It has winged lions carved into the legs of the stand. The exhibition stand done around 1858 helped put Gustav Herter on the map and would preface the brother’s success later in life.

The Herter Brothers manufactured numerous sets of armchairs, all of which were ornate and expensive; however, an armchair done in 1974 embodies a lot of the key principles seen in their chairs. The chair made for the James Goodwin residence in Hartford, Connecticut was rendered from rosewood, and oak, gilded, and upholstered in a plush, red silk. The arms of the chair end in roaring viciously. The back and seat of the chair is tufted. The feet of the chair are craved well and the piece as a whole is stunning. This was just one of the many armchairs designed by the men; armchairs were an important part of their franchise.

The Herter boys had a standard childhood during an explosive time in history that inevitably led to amazing furniture, which contributed positively to the interior architecture profession, society, and culture as a whole. Christian died in 1883 from consumption. Gustav died in his home on November 29, 1898 from old age. Without Gustav and Christian, artist still might have never thought to combine design from various cultures. The brothers helped to establish a sense of power in America. They also helped to fashion the notion of designing the whole room, a concept that is evident in design today. The Herter Brothers were key in shaping interior architecture today.